Last week, I wrote a piece about five of the key hires who took Morning Brew to $40 million in revenue.

I mentioned that I had a process for finding such people, and was surprised by how many of you were interested in hearing more about that.

So this week, I’m going to show you that process, but I want to ground it in something a little more important – namely, why look for these people in the first place?

Well, here’s why…

In any business, including the creative ones, there are really only three types of advantages you can have over your competitors:

Resources: You have money to burn, and they don’t

Behavioral: You naturally do something that they don’t

Information: You know something they don’t

When a writer buys $200,000 worth of their own book in order to guarantee it lands on the bestseller list (yes, this happens), that’s a resource advantage. They have enough money to manipulate the system, giving them an edge, even against people who may be better writers.

If someone writes compulsively, and just can’t help themselves, that’s a behavioral advantage. They have an edge over the person who has to force themselves to sit down and write.

Personally, I prefer an information advantage because I think it’s the only one you can choose to cultivate, and is most resilient to AI.

And when it comes to information, the biggest moat that you can have is access to people. Not famous people. But rather, the people behind the scenes who have just as much insight and far less attention.

Stephen Hanselman, Heather Jackson, Donna Passannante, Tara Gilbride, Ilena George, Lindsay Mecca, Kate Perkins Youngman, Laura Hurlbut.

Do you recognize any of those names?

Probably not, but they’re some of the first people that Tim Ferriss thanked in the acknowledgements section of The Four Hour Workweek, and they belong to his agent, editor, marketing director, and publicity director, respectively, along with the four interns who helped him get the project over the finish line.

Isn’t that interesting? The stories they could tell…

That book spent more than four consecutive years on the New York Times best-seller list, and fans like me default to giving Tim all the credit for that. But he himself considers these people absolutely crucial to the success of the project and we don’t even know their names.

And this is the big point – there’s an asymmetry between the people who have interesting experience and insight on any particular topic, and the people who get the attention.

It holds true in every arena. Every company. Every creative project. Attention flows like water towards a few people at the front. But for every CEO, or lead actor, or author, there are lots of people slightly behind the scenes who have just as much fascinating insight. Maybe more.

More?

Yes, maybe. Check this out…

A quick Google of Stephen’s name reveals that he didn’t just work with Tim on each of his five books. He also worked with other incredibly popular authors like travel writer Rolf Potts, investor Kamal Ravikant, and stoic Ryan Holiday.

Indeed, he’s actually a co-author of at least two of Holiday’s books.

So if everyone wants to write a story about how Tim Ferriss or Ryan Holiday became best-sellers, the path taken by most of your competitors will be to either…

Do a lot of Googling, and rehash other pieces or…

Try to contact the authors for (yet another) interview

An option that’d set you apart would be to reach out to people like Stephen.

Tim and Ryan are practically impossible to contact because of the volume of inbound they get. Stephen’s Gmail address is listed right on his Publisher’s Marketplace profile.

I think my old company, The Hustle provides an interesting example of how this works in practice.

Our main competitor was Morning Brew, and if you subscribe to both The Hustle and Brew, and a few other similar newsletters, what you’ll find is that maybe 40-60% of their daily coverage overlaps.

They report on the same stories, share the same links.

Why? Because everyone’s pulling from the same few information sources.

Running a multi-million dollar daily newsletter is all about efficiencies. Over time, each writer finds their favorite sources – a few places they’re guaranteed to find the stories readers want – and there are only a handful of those.

Then there was the Sunday Story.

The Sunday edition of The Hustle was refined by Zachary Crocket, and it sprang from his desire to do more in-depth, long-form coverage of business stories that were further off the beaten path. Things like…

You can’t just Google these kinds of things. That’s why they’re so interesting.

Zack spent his time combing through old newspapers, absorbing the comments in very niche Facebook groups, or rifling through long-forgotten boxes in the dark corners of museum archives.

Almost as a rule, he tried to avoid talking to big, well-known names. Instead preferring the people who were deep in the trenches, had lots of experience, and almost zero attention.

He wrote what no one else could because he looked where no one else would.

And he (read, “we”) were rewarded for it. The pieces were insanely popular. To this day, it’s common to surf Hacker News and see one of the old Sunday Stories from years ago trending on the front page again.

When you write what no one else can, people want to share.

I know I promised you my own personal method for finding these kinds of interesting employees in a company, so here it is…

I like LinkedIn.

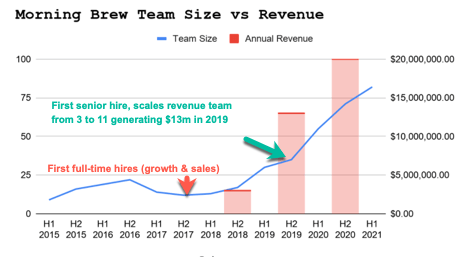

When I’m deconstructing a company, I start by reading a few interviews with the founders to plot the growth over time, along with any other major milestones.

I chart it so I can see any major turning points. For example…

Then, I search LinkedIn for everyone who’s worked at a place, or was hired around major turning points in a company, and manually plot their…

Name

Title

Department (Editorial, Sales, Operations, etc.)

Start/End Dates

…in a spreadsheet.

There’s probably a way to do this automatically with robots or VAs or something, but I do it manually because I find it gives me a much better feel for each person’s actual relationship with a company.

For example, on LinkedIn, someone may say they were CMO of a company for just three months, and if you take that data at face value, you may think something very bad must have happened for a company to hire and lose such an important role in so short a time.

But when you look closer, you see that this person was a sophomore in college at the time, that the company was just a month old, and that actually, it wasn’t so much an executive hire as it was kids trying to get something off the ground.

That sort of thing happens a lot when you study startups, and that’s why I do it manually.

At any rate, if you do this, what you’re left with is a map that shows how a company grew over time – where their hiring priorities were, and by extension, the major challenges or opportunities they were facing at any given point, as well as the people who played pivotal roles in their success.

It’s not perfect. Some people don’t keep their LinkedIn up to date. But it’s directionally accurate, and enough to give you the kind of look into a company you won’t typically find on TechCrunch.

Once you have that, there are two things you can do:

Sleuthing: I plug names of lesser-known key employees into Google and Spotify to see if they’ve talked about their work publicly at all – often, they have.

Consulting: A lot of people are happy to give you an hour of their time after they leave a company, and for $100 or so, you can learn things the original employer paid thousands to understand.

You don’t need many. In fact, most the time, all it takes is one name, and from there, you can find your way to the rest.

That’s the beauty of focusing on people - they have such rich context. A ten-minute chat can save you hours of research.

And so I’ll leave you with one more little tip I got from Zach when we worked together – something small that’s had a big impact on my work.

When finishing an interview, one of the last questions he always asked was, “Who else do you think I should talk to about this?”

It’s small. But you wouldn’t believe what comes from that.